aT the JARDIN des plantes (Paris)

The Romé de l'Isle - Haüy controversy: opposing strategies

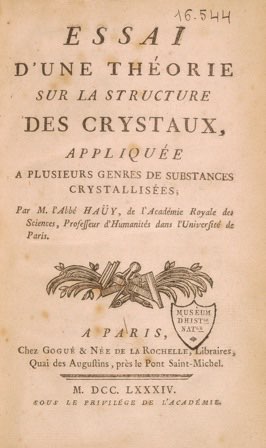

As an amateur botanist, René-Just Haüy (1743-1822) discovered crystals in 1780 between the Collège de France and the Jardin des Plantes, thanks to his mentor Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton (1716-1799). In his 1784 essay, René-Just postulates that crystals are made of a stack of small volumes of matter, Haüy's "integral molecules", which are characteristic of each mineral species. But unlike Romé, Haüy formalized various geometrical relationships between these "integral molecules" and natural crystals: these theories were immediately enthusiastically received. It is the glory! René-Just was appointed curator at the Ecole des Mines, then professor at the Muséum in 1802 and at the Faculty in 1809. During this time, he had hundreds of wooden crystal models made and shipped throughout Europe and even to America, spreading his "revolutionary" theories on crystallography.

This treatise will be the first great book of Haüy who wrote it when he was still teaching Latin at the College of the Cardinal Lemoine (demolished 1825) that used to belong to the Sorbonne University of Paris.

From this Sorbonne/Paris University College, Haüy had already published a number of brilliant articles on crystals: garnet, calcite etc.

These works opened him the doors (1783) of the Academy of Sciences (as assistant botanist!) then, in 1795, he is nominated at the French Academy of Sciences as « first class » mineralogist.

The same year he is nominated at the Paris’ École des Mines where he became the first curator of the mineral collection and professor of crystallography (1795).

René-Just Haüy: FROM THE JARDIN TO, EVENTUALLY, BACK TO THE JARDIN

Lire l’Essai d’une théorie... (1784)

Essai d’une théorie sur la structure des crystaux

Romé de L'Isle and Haüy both defined microscopic fundamental polyhedra that they called "integrating molecules". According to them, they aggregate to form macroscopic "primitive forms" that can be found in the simplest crystals. But their respective interpretations vary a lot:

- for Romé de l'Isle, there are 6 "integral molecules" that are the basis of all natural crystals, including the cube and the tetrahedron. But Romé de l'Isle forgets the hexagon and favors exhaustive descriptions.

- On the contrary, Haüy integrates the hexagon as one of its 6 primitive forms and seeks simplifications: he proposes that crystals are built according to various rational laws and on the basis of 3 of its "integral molecules": the distorted tetrahedron, the cube and the rhomboidal dodecahedron. This quest for simplicity - typical of Abbé Haüy - instantly contributed to his triumph!

Alexander Roslin : Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton (1791) Orléans, Musée des Beaux-arts/©wiikimedia

Jean-Baptiste Hilair: Le cèdre du Jardin du roy (The Cedar At the King’s Garden, circa 1794). ©BnF

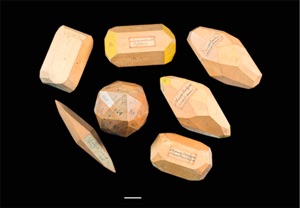

Wooden crystal models in pearwood and annotated following the Tableau méthodique by Daubenton, mentor of Haüy, editon of 1792. Scale bar 1 cm. Paris, MNHN, minéralogie. Photos: F. Farges.

With Johan Kjellman, we have rediscovered wooden models annotated by Daubenton according to its 1792 Tableau méthodique at a time Haüy was still at the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine and, thus, before he entered at the Paris’École des Mines where Pleuvin (father) worked as a carpenter/cabinetmaker for creating Haüy’s well-known large series of crystal models.

Maybe these Daubenton models, their maker remaining unknown, inspired Haüy to start creating his own at the École des Mines, then at the Jardin des plantes.

Its is important to realize that Haüy did his first and more decisive discoveries while he was (translated) "Professor in Humanities" at the College du Cardinal Lemoine, protected by Daubenton at the Paris’ Jardin des plantes.

Alfred Bonnardot

Remains of the Collège du Cardinal-Lemoine (1841). ©Paris, Musée Carnavalet, D.11556.

But Haüy will stay at the École only six years, before being nominated « Professeur du Muséum », a sort of « return to the roots », following the premature death of Dolomieu in 1801 whose courses he taught on an interim basis at the Jardin des Plantes from 1800 onwards.

René-Just is then nominated professeur at the Paris university in 1809 but that was François Sulpice Beudant that actually taught his lectures there.

Modèles de cistaux en bois de poirier de la collection personnelle d’Haüy, probablement fabriqués à l’École des mines. L’échelle vaut 1 cm. Paris, MNHN, minéralogie. Photos : F. Farges.

Haüy will be the third holder of the chair of mineralogy at the Museum (after Daubenton and Dolomieu because it was created in 1793) and the first holding the chair at the university (created in 1809).

It is unfortunate that very little remains of Haüy's material legacy at the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine, the École des mines de Paris and the university (faculty of science): many specimens and tools have been destroyed, lost, used for experiments, exchanged with other specimens or have lost their labels allowing them to be identified again.

Various other institutions such as the Freiberg School of Mines and a few others (Tyler Museum in Haarlem in the Netherlands, etc.), preserve many of Haüy's objects, but the major part of his material legacy is essentially preserved at the Paris’ Jardin des Plantes, i.e. the current MNHN, following the (smart) purchase of Haüy’s personal collection in 1848 from the heirs of the Duke of Buckingham.

Charles Howard Hodges: portrait of Martinus van Marum (ca. 1826), curator at the Tyler Museum in Haarlem (Netherlands) and one of Haüy's many correspondents ©wikimedia

One of the wooden models purchased from Haüy by Martinus van Marum and kept at the Tyler in Haarlem ©wikimedia

Daubenton reports, in his 8th lesson at the École normale of the Year III that Haüy:

...fit, en 1780, ses premières observations sur les cristaux, en suivant mon cours de minéralogie au Collège de France ; je me sais bon gré de l’avoir soutenu contre son extrême modestie, en l’exhortant à rédiger ses observations ; il y a plusieurs mémoires du citoyen Haüy sur les cristallisations dans le recueil de l’Académie des sciences. Il publia, en 1784, son essai sur la structure des cristaux. Il en fit un résumé en 1793 ; je simplifiai ce résumé ; je l’abrégeai, pour la commodité des étudiants du Collège de France [...] Le citoyen Haüy a surmonté toutes les difficultés qu’il y avait à franchir, pour concevoir la théorie des cristallisations, et pour en donner des preuves physiques et mathématiques. »

...made, in 1780, his first observations on crystals, while following my course of mineralogy at the Collège de France; I am grateful to have supported him against his extreme modesty, by exhorting him to write down his observations; there are several memoirs of the citizen Haüy on the crystallizations in the collection of the Academy of sciences. He published, in 1784, his essay on the structure of crystals. He made a summary of it in 1793; I simplified this summary; I shortened it, for the convenience of the students of the College of France [...] The citizen Haüy overcame all the difficulties which there was to cross, to conceive the theory of the crystallizations, and to give physical and mathematical proofs of it."

Haüy, like you and me, never did anything alone: his mentor Daubenton, at the Jardin des plantes, will quickly be surpassed by its student»