FROM Paris TO LONDON,

FROM Buckingham TO THE JARDIN

THE HAÜY COLLECTION SOLD TO THE DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM

Haüy had refused to sell his collections to princes to give them to the Museum.

Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) pronounces his eulogy by inventing the story of the calcite which Haüy would have made fall by clumsiness and, in the tread, finds his theory of the rational decreases.

HOMECOMING

After the death of the Duke of Buckingham riddled with debts, its properties are sold: it will be one of the first major sales of Christie's.

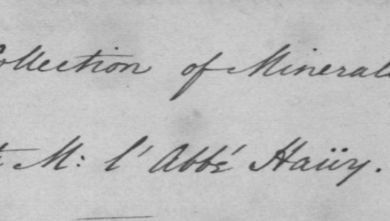

In the sale catalog, the Haüy collection is priced to know the almost 9 000 samples of minerals, rocks, models, crystals and a portrait and a collection of amber but from a certain "Captain Nevill" of the Royal Navy. As well as the display cases containing these specimens.

G. Romneye : Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville (1t Duke of Buckingham and Chandos)(before 1800)

But it is too late, the collection has been sold for the staggering sum of 100 000 francs to Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, first Duke of Buckingham and Chandos (1776-1839).

More seriously, this same Cuvier informs the administration of the Museum that there are four Haüy collections: minerals, rocks, wooden models and gems.

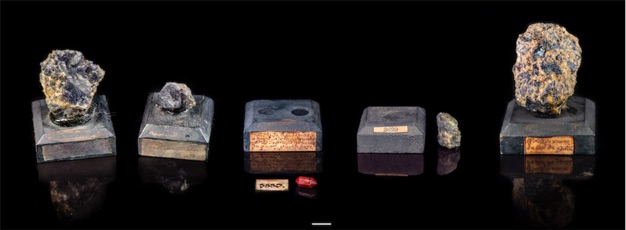

Minerals and gems are mounted on black wooden bases with Judean bitumen to support the specimens. In addition, it specifies that the gems are, moreover, mounted in gold.

Shortly after his death, the MNHN offered his nephews, daughter and son of his brother Valentin, 50 000 francs for the purchase of his personal collection.

Armand Dufrenoy (1792-1857), a convinced anglophile and Professor of the MNHN, went to London and acquired the collection for 325 pounds sterling and 10 shillings on behalf of the "Directors of the Jardin des Plantes" [sic!].

The Museum also succeeded in recovering the collection through the intermediary of a French entrepreneur from the Nièvre, central France, Émile Martin (1794-1871), owner of foundries at the Garchizy-Fourchambault complex (near Nevers) and also established in London, who advanced the funds, i.e. 12,094 francs for the purchase and various expenses as well as 2,110 francs for transport from London to Paris.

The memory of Émile Martin has been forgotten since then but it is my role here to restore it, especially since my great-grandfather, François Pliquet, from whom I take my first name, was a mineral chemist there.

ARCHIVES

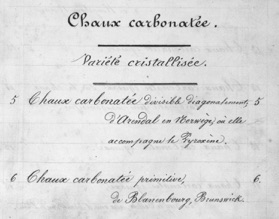

The collection will be re-labeled by Dufrenoy as well as its catalog translated into French which allows, nowadays, to know the texts of the labels inscribed by Haüy on the bases, some of which have since been erased or lost.

Because the Haüy collection, as well as that of Romé de L'Isle's models, was exposed for a long time in the vestibule of the Grande Nef de Minéralogie, which altered the metallogallic inks.

Overview of the hallway of the mineralogy nave (by Pierre Petit, near 1895) showing the two display cases of Romé de L'Isle's models (around the large central door) and, further away, two of the large oblique display cases containing the Haüy collection.

The gems will be removed from their wooden bases, sometimes in a wild way, with the secateurs. Fortunately, the bases were kept and I put them back with the gems in 2019.

On the other hand, thousands of specimens were recently removed for conservation purposes... and their Judean bitumen thrown away before we could intervene, informed of this vandalism, to stop this misery.

GREAT NEWS!

We do not know for sure if the portrait that accompanied the Haüy collection sold by the Buckingham heirs in 1848 was this anonymous and undated painting that resided for a long time in the mineralogy laboratory of the Museum before being entrusted to the Central Library.

This portrait is very similar to the one painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1808 in Paris. It is known that he made a copy in 1809 in Philadelphia and that he sent it to Haüy, whose niece was impatient to see it (letter found by J. Kjellman in Berlin).

Worrying about cordierites from the Haüy collection: on the left, two preserved cordierites with their black Judean bitumen to base them; on the right three recently deteriorated. The middle one had already lost its sample, borrowed by a researcher at an unknown date but not put back in place and probably lost except for a hematoid quartz crystal. On its right, a crystal that cannot be put back in place, its Judean bitumen having been totally eliminated, in contrast to the one on the far right which still has a trace of bitumen on the specimen, which allows us to imagine a reconstitution of the original set-up intended by Haüy. But for hundreds of specimens, the information is irretrievably lost. The scale bar is 1 cm. Paris, MNHN, mineralogy. Photos: F. Farges@MNHN.

OTHER SUFFERINGS

The amber collection known as « Haüy's » bears only a few gold-set ambers as shown right.

This corpus is often confused with a much larger collection, in reality Captain William Nevill (Esa. Winchester) of the Royal Navy (dates unknown, active 1800-1825). He collected them on Saint-Brandon Island, or Cargados Carajos Shoals, located north of Mauritius Island in the Indian Ocean. That amber corpus was acquired by Buckingham and sold in 1848 together with the Haüy collection.

Those ambers were savagely glued on plastic bases in the 1950s. Some were restorated by removing the enormous excesses of glue.

Unsigned portrait of Haüy permissibly attributable to Rembrandt Peale, Philadelphia, 1809, possibly the one mentioned in the 1848 sale. Paris, MNHN, Bibliothèque centrale.

Many of these recent discoveries and restorations were shown in a special showcase in the "Pierres précieuses" (Gems) exhibition at the Jardin des plantes in 2020-2021 for which I was scientific curator, with Lise MacDonald of Van Cleef & Arpels, the main sponsor of this event..

Showcase of the third part of the exhibition "Pierres précieuses" (Gems) at the Jardin des plantes in Paris (2020-2021) showing the contribution of Haüy to mineralogy (left), crystallography (center) and gems (right).

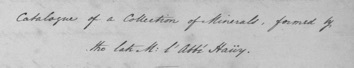

First page of the catalog of the Haüy collection translated into French by Dufrenoy.

A Captain Nevill’s amber restored from its infamous 1950s collage.

Some gold-set ambers of the Haüy collection. Paris, MNHN, minéralogie.

The collection is preserved as well as possible : still, some pyrites are already reported as decaying. Buckingham offered Haüy's own goniometer as a gift to Dr Buckland who eventually gave it, I assume, to an Oxford University museum, possibly the mineral collection of the Oxford university’s Museum of natural history despite our researches did not succeeded yet:

The personal goniometer of Haüy, clearly in a museum of the Oxford museum (our researches about it did not succeeded so far).

After his death, his heirs did not fulfill his wishes to give his collection to the Museum but sold it to the English. Luckily, for a limited time...